According to legend, experts said for years that the human body was incapable of running a four minute mile. It wasn’t just dangerous; it was impossible.

During the 1940s, the record was pushed to 4:01 where it stood for nine years but on May 6, 1954, Roger Bannister broke the 4 minute barrier with at time of 3:59.4. He broke it because he believed he could with a regimen of relentlessly visualizing the achievement in order to create a sense of certainty in his mind and body.

In most things, whether you believe you can or cannot, you are correct. If you believe in yourself or in the eventual attainment of a goal, it may take some time, but you can make it happen.

Then why is a generation of economists and finance professors teaching that it’s near impossible to succeed in the world of finance?

Why Do They All Seem to Graduate from the Same School?

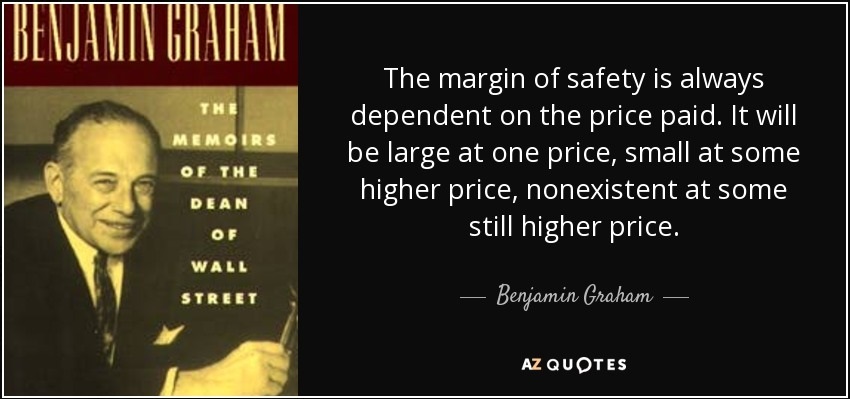

Columbia Business School has graduated many of the brightest investment minds of this past century. Is it because of what they teach or the quality of the students? I would argue the former. The father of value investing, Benjamin Graham just happened to teach students such as Sir John Templeton, Bill Ruane, Walter Schloss, Charles Brandes and Warren Buffett. He taught them to value businesses and buy those where a “Margin of Safety” exists between the market value and what you have figured is the business’ intrinsic value.

Most business schools teach to the Efficient Market Theory. If the market is efficient it must be best to keep expenses as low as possible. When it comes to money managers, does it make any difference to study the horses in the race? Do we want to believe that Secretariat’s success is just a statistical anomaly and it is impossible to find a horse that consistently wins? Do we want to abandon the study of the horses and just look for the lightest jockeys? Horse-racing enthusiasts like to say that the jockey accounts for 10 percent of a horse’s performance on any given day. While that’s hardly scientific, it gets to the nut of a jockey’s role: He can’t do much with a lousy horse, but he can help a great horse win. One school of thought in investing today is that the jockey makes all the difference when it comes to investing and that all horses are statistically the same. Another school of thought is that you can find and train the best horses and that the jockey is less important.

Evidence for Inefficiency

To quote Louis Lowenstein from his 2004 paper Searching for Rational Investors In a Perfect Storm. “The speculative excesses of the ‘90s threw a harsh light on efficient market theory (EMT), which for decades has been a cornerstone of economic theory and scholarship. No Business School student has escaped it; no economics professor has won tenure without paying his respects. EMT has also had significant impact on public policy and investment practices. It is, indeed, an appealingly simple idea, that in order to make money in the stock market one must compete against the “smart money,” the so-called rational investors, who are constantly scouring the market for opportunities. Because of them, all relevant new information is quickly captured by the market. No point in doing research oneself. Trust prices; the rational investors will already have erased most any discrepancy between price and value. Since you cannot beat the market, buy a diversified portfolio, say the Standard & Poor’s 500 index fund, and save yourself the cost and sweat of an actively traded account.

Obviously the theory was wrong – woefully so. In the late 1990s, stocks soared to levels out of all proportion to their underlying values, indeed to levels well beyond even the excesses of the 1920s. If the NASDAQ Composite Index, for example was right at 1200 in April 1997, it surely wasn’t right at 5000 in March 2000, and then right again at 1100 two years later. (The rise and then almost 50% decline of the broader based S&P 500, though widely noted, was also stunning.)”

Proponents of efficient markets would also tell us that mortgages were priced correctly in 2007 and early 2008. How could this be if only a few months later a great swath of them were deemed to be worthless when the “news” was finally received.

People continue to hold to their flawed thinking for far longer than they should. We become blind to change, we look for confirmation for our theories when the evidence supports a different view. We are influenced by the noise and let “Mr. Market” affect us with his moods. Because we are all human some would say we are programmed to make these mistakes due to our inherent biases. We covered many of these biases in our Brain Games workshop last week.

Are we in Danger of Another Lost Decade?

We are now in year eight since the bottom of the financial crisis. From 1928 until today we have only seen one bull market last longer than our current one and only a third have seen moves of larger magnitude. My career started in the midst of the longest lasting and possibly most irrationally exuberant bull markets since the roaring twenties and I cannot help but notice some of the similarities between then and now.

If you want to look at where the bubbles are developing, just look at where the assets are flowing. In 2009, bonds and money markets became the most popular asset class at the same time equity markets around the world were offering up the best opportunities most of us will probably see in our lifetimes. But what we are experiencing now has much more in common with the late 1990s. Starting in 1996 and 1997 investors poured money into large company U.S. equities, specifically the S&P 500 and largely abandoned diversification, culminating with the dot-com craze of 1999.

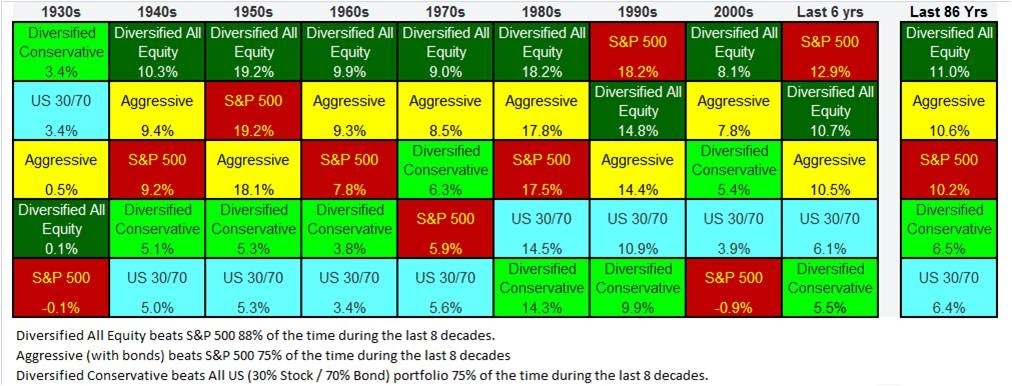

Looking at the chart above, we can notice that in seven of the last eight decades, a diversified all-equity portfolio posted better returns than the S&P 500 index and the one decade where the index fared better was followed by the worst relative performance of any decade. Unfortunately the out-performance of the S&P 500 and particularly the Nasdaq 100 led to the lost decade of the 2000s with these same indexes failed to post positive returns.

Bill Ackman, wrote in his letter to investors last year how he was concerned about a bubble in indexing that he felt could lead to lack of accountability to shareholders and markets that could look more and more like Japan’s over time. Bernstein also wrote a piece late last year that came to similar conclusions, While we believe that indexing can be particularly helpful in taxable accounts to gain diversification in a tax efficient manner, we are definitely concerned about the current level of popularity creating bubbles in various areas of the markets.

As can be noted in the chart, those who were better diversified in the 2000s did not suffer with the crowd. They may have been thought to be out of step during the dot.com craze but fared much better in the years to come.

When should we be concerned?

What do the Peter Lynch (1980s), Bill Gross (2000s), John Bogle (1990s) and Warren Buffett (1960s) all have in common? They all raised significant assets during their heyday and the manager either retired or greatly underperformed during the subsequent period. I would be more wary of a manager that brings in the most assets and fails to caution investors that this popularity may be a warning sign.

Many money managers will continue to take in more funds even in the face of diminished future returns but others will close their doors temporarily to new investors in order to better serve current investors. Toward the end of last year, we saw quite a few managers we have entrusted funds with that have done this and we appreciate them for putting the investors interests first.

We respect Buffett for not only closing his doors in 1969 and returning funds to shareholders but also referring them to Bill Ruane and helping the remainder find good bond options at appealing prices.

In talking about Bill Ruane in his 1968 letter to investors, Buffet states, “We met in Ben Graham’s class at Columbia University in 1951 and I have considerable opportunity to observe his qualities of character, temperament and intellect since that time. If Susie and I were to die while our children are minors, he is one of the three trustees who have carte blanche on investment matters.

Bill’s overall record has been very good-averaging fairly close to the Buffet Partnership’s but with considerably greater variation. In 1962, undoubtedly somewhat as a product of the euphoric experience of the earlier years, he was down about 50%. As he reoriented his thinking, 1963 was about breakeven.

While two years may sound like a short time when included in a table of performance, it may feel like a long time when your net worth is down 50%. I think you run this sort of short term risk with virtually any money manager operating in stocks and it is a factor to consider in deciding the portion of your capital to commit to equities. To date in 1969, Bill is down 15%, which I believe to be fairly typical of most money managers.”

Bill Ruane passed away, but the characteristics of the best managers remain and we look for these qualities in all managers we choose. Buffet also outlined many of the characteristics he values in managers in his piece, “The Super-investors of Graham and Doddville.”

The Best Managers tend to:

- Eat their own cooking (invest in the same holdings as their clients)

- Be proven to protect in down markets

- Have lower turnover (less than the 100% per year average we see currently)

- Have the right temperament (not be influenced by fear, greed or what is popular) – indexing is definitely popular now

- Own a more concentrated portfolio (30 or less individual positions is common)

- Be disciplined (have a strategy and stick to it without deviation)

Speaking of discipline, after Buffett published “The Super-investors,” the calculations showed that while they were indeed super-investors, on average they had trailed the market one year in three. Lowenstein, in his “Rational Investors” paper determined that of his sample of ten, “new super-investors”, four of them had each under-performed the S&P 500 for four consecutive years, 1996-1999, and in some cases by huge amounts. For the full ten years, of course, that under-performance was sharply reversed, and then some. Successful investing thus requires not just patient managers but also patient investors, those with the temperament as well as intelligence to feel comfortable even when sorely out of step with the crowd. As of late 2015, many of these managers may have also felt out of step. For most of them, this was a temporary phenomenon as the markets recovered in 2016. Unfortunately, we still feel a bubble forming in indexing and treasuries that may lead us to a repeat of the “Lost Decade”. To avoid this we need to maintain discipline, stay diversified and make sure to retain the right temperament in the face of increasing euphoria.

Joe D. Franklin, CFP is Founder and President of Franklin Wealth Management, and CEO of Innovative Advisory Partners, a registered investment advisory firm in Hixson, Tennessee. A 20+year industry veteran, he contributes guest articles for Money Magazine and authors the Franklin Backstage Pass blog. Joe has also been featured in the Wall Street Journal, Kiplinger’s Magazine, USA Today and other publications.

Important Disclosure Information for the “Backstage Pass” Blog

Please remember that past performance may not be indicative of future results. Indexes are unmanaged and cannot be invested into directly. Index returns do not reflect fees, expenses, or sales charges. Index performance is not indicative of the performance of any investments. Different types of investments involve varying degrees of risk, and there can be no assurance that the future performance of any specific investment, investment strategy, or product (including the investments and/or investment strategies recommended or undertaken by Franklin Wealth Management), or any non-investment related content, made reference to directly or indirectly in this blog will be profitable, equal any corresponding indicated historical performance level(s), be suitable for your portfolio or individual situation, or prove successful. Due to various factors, including changing market conditions and/or applicable laws, the content may no longer be reflective of current opinions or positions. Moreover, you should not assume that any discussion or information contained in this blog serves as the receipt of, or as a substitute for, personalized investment advice from Franklin Wealth Management. To the extent that a reader has any questions regarding the applicability of any specific issue discussed above to his/her individual situation, he/she is encouraged to consult with the professional advisor of his/her choosing. Franklin Wealth Management is neither a law firm nor a certified public accounting firm and no portion of the blog content should be construed as legal or accounting advice. A copy of Franklin Wealth Management’s current written disclosure statement discussing our advisory services and fees is available for review upon request.