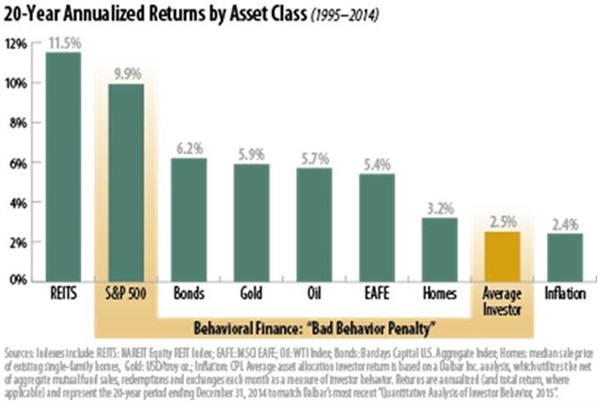

Last week we hosted our first session of Brain Games in which we found as many ways as we could to trick the audience. We unveiled to them their own biases and ways their own instincts work against them, especially when it concerns investing. It’s especially interesting to see how most people believe that they cannot be tricked or do not have these biases until it becomes painfully obvious to them. Others are better able to overcome many of these detrimental instincts which unfortunately sometimes leads to the most pervasive biases of many professionals: Over-confidence, optimism and confirmation bias (see below). Many may not want to admit they have these biases while others, looking to truly improve themselves and their future, will search for the truth. The results bear out that most are not aware of their own blind spots and left to their own devices, fare much worse than they would otherwise (see chart below).

These are not all the biases that we encounter, but these are the ones that we see hurting investors most often. Your suggestions of important ones I have missed are welcome.

- Confirmation Bias. We like to think that we carefully gather and evaluate facts and data before coming to a conclusion. But we don’t. Instead, we tend to suffer from confirmation bias and thus reach a conclusion first. Only thereafter do we gather facts and see those facts in such a way as to support our pre-concieved conclusions. When a conclusion fits with our desired narrative, so much the better, because narratives are crucial to how we make sense of reality. A fun video which shows us how we miss the things we do not expect to see can be found here.

- Overconfidence & Optimism Bias. This is a well-established bias in which someone’s subjective confidence in their judgments is reliably greater than their objective Indeed, we live in an overconfident world. We are only correct about 80% of the time when we are “99% sure.” Fully 94% of college professors believe they have above-average teaching skills (anyone who has gone to college will no doubt disagree with that). Since 80% of drivers say that their driving skills are above average, I guess none of them drive on the freeway when I do. While 70% of high school students claim to have above-average leadership skills, only 2% say they are below average, no doubt taught by above average math teachers. In a truly terrifying survey result, 92% students said they were of good character and 79% said that their character was better than most people even though 27% of those same students admitted stealing from a store within the prior year and 60% said they had cheated on an exam. Venture capitalists are wildly overconfident in their estimations of how likely their potential ventures are either to succeed or fail. In another finding 85-90% of people think that the future will be more pleasant and less painful for them than for the average person.

Source for image: http://www.fakeposters.com/

Source for image: http://www.fakeposters.com/ - Loss Aversion. We are highly loss averse. Empirical estimates find that losses are felt between two and two-and-a-half as strongly as gains. Thus the disutility of losing $100 is at least twice the utility of gaining $100. Loss aversion favors inaction over action and the status quo over any alternatives. Therefore, when it comes time for us to act upon the facts and data we have gathered and the analysis we have undertaken about them, biases 2 and 3 – unjustified optimism and unreasonable risk aversion – conflict. As a consequence, we tend to make bold forecasts but timid choices.

- Herding. We all run in herds — large or small, bullish or bearish. Especially in volatile times, many investors feel pain when they go against the herd and hold tight during a period when the crowds are fearful and selling. Others are able to overcome this and buy when the best bargains are available and sell when things get too pricey. It sounds easy, but much harder in practice to overcome these instincts. Institutions herd even more than individuals in that investments chosen by one institution predict the investment choices of other institutions by a remarkable degree. Even hedge funds seem to buy and sell the same stocks, at the same time, and track each other’s investment strategies. That affinity fraud (e.g., Bernie Madoff fleeced the Jewish community to which he belonged) is so common is definitive evidence of herding.

- Self-Serving Bias. Our self-serving bias is related to confirmation bias and optimism bias. Self-serving bias pushes us to see the world such that the good stuff that happens is my doing (“we had a great week of practice, worked hard and executed on Sunday”) while the bad stuff is always someone else’s fault (“It just wasn’t our night” or “we simply couldn’t catch a break” or “we would have won if the refereeing hadn’t been so awful”).

- Choice Paralysis & Information Overload. Intuitively, the more choices we have the better. However, the sad truth is that too many choices can lead to decision paralysis due to information overload. Computers are great at factoring hundreds of variables for an optimum result but the human brain can usually only handle four of five key variables well. For example, participation in 401(k) plans among employees decreases as the number of investable funds offered increases. We are readily paralyzed by too many choices.

- Availability / Recency Bias. We are all prone to recency bias, meaning that we tend to extrapolate recent events into the future indefinitely. I would not recommend watching Jaws and Shark week just before going to the beach. I would also not recommend watching too much CNBC as it may cause much the same over-reaction to the markets and cloud your thinking. As reported by Bespoke, Bloomberg surveys market strategists on a weekly basis and asks for their recommended portfolio weightings of stocks, bonds and cash. The peak recommended stock weighting came just after the peak of the internet bubble in early 2001 while the lowest recommended weighting came just after the lows of the financial crisis. That’s recency bias. Short term thinking.

- Anchoring & the Sample Size Fallacy. These biases are closely tied to the availability or recency bias. After Peyton Manning injured his neck and missed the entire 2011 season, many thought he may never perform at the same level again, despite the long track record of success that he had established in the NFL. The 2012 season showed that he could still play, but many still felt that his best playing days were behind him. All of this changed in the 2013 season when he opened the season with one of the most prolific passing games of all time against the defending Super Bowl Champions and finished the year breaking the previous records for touchdowns, points scored and passing yards. Many people look at a bad period and extrapolate this into the future thinking it will not be long until they run out of money or a good period and get overly confident. Many asset managers are judged by looking at the last year or even three years rather than taking a larger sample size to assess how they have done in good and bad periods.

- Familiarity Bias. Of course everyone remembers WorldCom and Enron from the early 2000s and how through accounting manipulations they were able to fool the masses and enjoy soaring stock valuations. In fact the people at the top of these companies were encouraging employees to buy the stock while they were selling when the end was near. And many were more than willing to hold a huge percentage of their retirement and buy more because they were very familiar with these companies. Many ignored wise counsel to diversify or limit their risk because they felt comfortable where they were, at least until they realized the end was near.

- We Prefer Stories to Analysis. As noted above, narratives are crucial to how we make sense of reality. They help us to explain, understand and interpret the world around us. They also give us a frame of reference we can use to remember the concepts we take them to represent. Perhaps most significantly, we inherently prefer narrative to data — often to the detriment of our understanding. Keeping one’s analysis and interpretation of the data reasonably objective – since analysis and interpretation are required for data to be actionable – is really, really hard even in the best of circumstances. A corollary to this problem and to confirmation bias is what Nassim Taleb calls the “narrative fallacy” — looking backward and creating a pattern to fit events and constructing a story that explains what happened along with what caused it to happen.

- The Planning Fallacy. In his terrific book, Thinking, Fast and Slow, Nobel laureate Dan Kahneman outlines what he calls the “planning fallacy.” It’s a corollary to optimism bias and self-serving bias. Most of us overrate our own capacities and exaggerate our abilities to shape the future. The planning fallacy is our tendency to underestimate the time, costs, and risks of future actions and at the same time overestimate the benefits thereof. It’s at least partly why we underestimate bad results. It’s why we think it won’t take us as long to accomplish something as it does. It’s why projects tend to cost more than we expect. It’s why the results we achieve aren’t as good as we expect.

- The Bias Blind-Spot. Of course there are many more cognitive biases which plague us and make it difficult for us to make good choices. Knowing about them is imperative if we are going to deal with them. We would always be wise to factor in these biases when performing analysis and making decisions. Unfortunately, we all tend to share a “bias blind spot” — the inability to recognize that we suffer from the same cognitive distortions that plague other people.

Learning which of these common behavioral biases and detrimental instincts you are susceptible to can greatly enhance your ability to plan for and overcome them.

If you have not assessed yourself for these pitfalls, we strongly encourage you to join us for our next Brain Games session.

For dates and times, please follow this link.

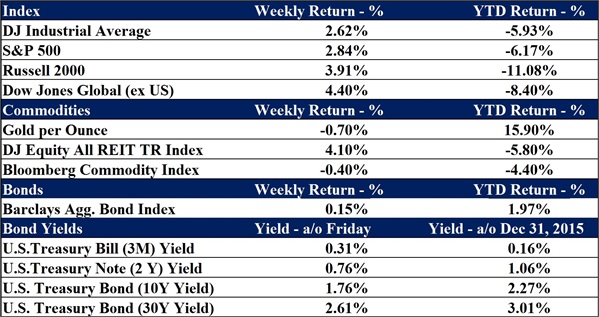

Data as of 2/19/2016

Joe D. Franklin, CFP is Founder and President of Franklin Wealth Management, a registered investment advisory firm in Hixson, Tennessee. A 20-year industry veteran, he contributes guest articles for Money Magazine and authors the Franklin Backstage Pass blog. Joe has also been featured in the Wall Street Journal, Kiplinger’s Magazine, USA Today and other publications.

Important Disclosure Information for the “Backstage Pass” Blog

Please remember that past performance may not be indicative of future results. Indexes are unmanaged and cannot be invested into directly. Index returns do not reflect fees, expenses, or sales charges. Index performance is not indicative of the performance of any investments. Different types of investments involve varying degrees of risk, and there can be no assurance that the future performance of any specific investment, investment strategy, or product (including the investments and/or investment strategies recommended or undertaken by Franklin Wealth Management), or any non-investment related content, made reference to directly or indirectly in this blog will be profitable, equal any corresponding indicated historical performance level(s), be suitable for your portfolio or individual situation, or prove successful. Due to various factors, including changing market conditions and/or applicable laws, the content may no longer be reflective of current opinions or positions. Moreover, you should not assume that any discussion or information contained in this blog serves as the receipt of, or as a substitute for, personalized investment advice from Franklin Wealth Management. To the extent that a reader has any questions regarding the applicability of any specific issue discussed above to his/her individual situation, he/she is encouraged to consult with the professional advisor of his/her choosing. Franklin Wealth Management is neither a law firm nor a certified public accounting firm and no portion of the blog content should be construed as legal or accounting advice. A copy of Franklin Wealth Management’s current written disclosure statement discussing our advisory services and fees is available for review upon request